America, Between Dreams and Disenchantment

21.9 – 23.11.2025

Selected works from the Dionisio Gavagnin Collection and photographs by Valerio Geraci

Curated by

Steve Bisson e Dionisio Gavagnin

Orari

Sunday 4:30pm–7:30pm

On Friday, September 19th at 9:00 PM, in Treviso, Lab27 will inaugurate its 2025/2026 exhibition program with America, Between Dreams and Disenchantment, a show that questions what America still represents today for the Western imagination—an imagination that continues to chase its evolutions, myths, and drifting trajectories.

The exhibition weaves together historical perspectives from the Dionisio Gavagnin Collection—an archive preserving icons of 20th-century American photography—with more contemporary visions from American Eden by Valerio Geraci, who, since 2016, has been driving across the United States in search of the essence, contradictions, rugged beauty, and myth-making force that has fascinated him since childhood.

This is not a linear exhibition, but an elliptical vision, made up of counterpoints, echoes, and connections between past and present. A visual vocabulary built around concepts that for decades have fueled literature, cinema, and above all photography—and which today seem to have reached a critical turning point.

The Pioneer Spirit. It begins with the journey into the unknown: the myth of the frontier, the wagon and the horse as archetypes of a founding epic. A diptych pairing Walker Evans (1933) and Geraci (2023), ninety years apart, reveals a surprising continuity of intent: a gaze towards the margins, a tension toward a truth hidden in the folds of the everyday, where a spirit of assertion and triumph resides. The aesthetic language changes, but the stance of the gaze remains.

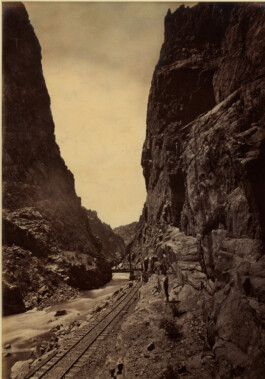

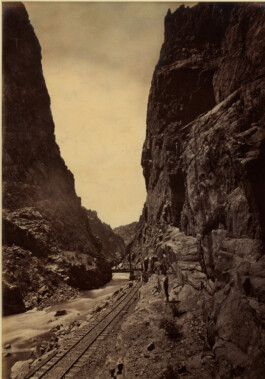

The Promised Land. America as an original Eden: vast, open, to be conquered. A place of hope and ambition. The photographs of O’Sullivan, Jackson, Curtis, and Weston span from 1874 to 1937, offering iconic visions of a nature encountered with a calculating, probing, documentary gaze. This is a prelude to the transformation in how the world would be perceived through the machine—leading up to Geraci’s 2021 photograph, in which a ribbon of asphalt winds like a snake through Utah’s monumental landscape: a powerful image of the gradual erosion of that primal innocence.

The act of looking—manipulating, cataloging, normalizing—reappears in the serial, industrial approach of Joseph Dankowski, who systematizes vision and anticipates digital exegesis through the reproducibility of his manhole covers (1969–1971). Decades later, Geraci playfully echoes this with a vernacular shot in Saint Martinville.

The Myth of Progress. From conquering the land to conquering asphalt: progress, as a salvific narrative, is questioned through images showing the alienating transformation of the landscape. Robert Frank’s (1955) anonymous parking lots of postwar commercial settlements give way to Geraci’s equally desolate tourist lot near Nevada’s Hoover Dam (2016). Already in 1947, Esther Bubley took us aboard a Greyhound bus—symbol of a coast-to-coast America—where travel becomes transit in a geography already colonized by the gaze.

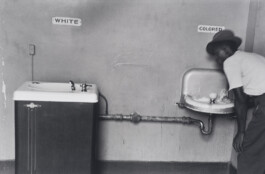

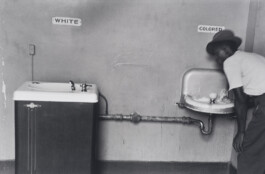

But there is another speed: that of those who do not take part in the race, or are excluded from it. The man in Elliott Erwitt’s North Carolina photograph (1950) and the one Geraci captures in Louisiana (2018) could be the same: hat, white shirt. A temporal diptych balanced by Mydans’s 1936 portrait of a couple in a stark rural Ohio interior. Once again, the provinces—the same that Geraci traverses—not by chance, but by choice: because here the heartbeat of deep America is most authentic and most overlooked.

When the Myth Becomes Symbol. In 1978, Joel Meyerowitz photographed a McDonald’s sign next to the American flag: two superimposed icons marking the shift from collective dream to individual consumption. The dream has been co-opted by hamburger culture—now brand, consumption, industry. Decades later, Geraci records its stubborn persistence: another McDonald’s, in Yuma, Arizona, where the landscape has been bent to a functional, homogenizing grammar. Here, the figure of a father—undressed in the half-light of a Tennessee motel room (2017)—becomes a meditation on the human condition, much like the bare gaze of Kee, a boy reclining before Nan Goldin’s lens (1988).

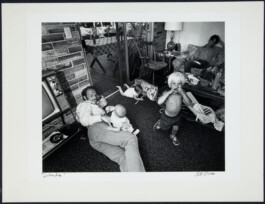

Television as a tool for shaping the masses and disseminating the myth—once the queen of the living room and the collective imagination. Stephen Shore’s TV (1975) is centered in the frame, dominating the scene. In Geraci’s work, however, it’s relegated to a vacant storefront in Mississippi (2017), tucked in a corner: switched off, forgotten, supplanted by the pocket-sized stream of social media. The intrusion of television as a prelude to the dematerialization of imagery under the panopticon of Big Tech.

For some, the American Dream is now a mirage—or a source of protest. In Joe Deal’s 1978 photo, the abstraction of a roadscape foreshadows contemporary chaos, a deranged cartography echoed in Geraci’s overturned car in Nebraska (2018), stranded off-road. In 1975, Lee Friedlander wryly confines monumental America to a traffic circle—an involutionary historical loop. Joel Sternfeld, in 1984, shows us the face of a blind man in Alaska’s outposts, surrounded by a lush garden he cannot see—anticipating the paradoxical mood of a West at sunset, edging into darkness. The gaze of a middle-aged man Geraci meets in Wyoming (2017) turns elsewhere—away from the photographer, away from the photograph—seizing, in its intensity, the blue of the skies.

In 1965, Diane Arbus photographed a family at a nudist competition: the dawn of a body revolution. A body that would be legitimized, commodified for entertainment. Today, that body is spectacle, product, performance. Geraci’s Texas cheerleaders (2018), dressed as cowboys and bathed in golden light, seem to stage a new choreography of desire and conformity. Between eros and marketing, the individual has become their own image.

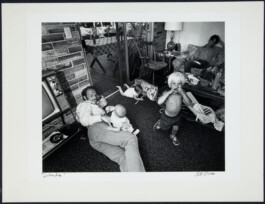

Family and Home. Foundational symbols of the American bourgeois imagination. Dorothea Lange (1935) captures, in the midst of the Dust Bowl, a family along the highway: uprooted yet united in desperate togetherness—tragically real. In 1972, Bill Owens takes us into suburban America, where the aspirations of the middle class find refuge and expression. And, in his own way, Geraci encounters a family and a home in Brady, Nebraska (2023), photographing them in the intimacy of Christmas decorating: a moment at once sacred and profane, reassuring and precarious—a reminder that family stability is fragile, yet capable of withstanding unforeseen challenges.

Valerio Geraci’s editorial project American Eden does not claim to offer an exhaustive reading of America, but rather opens a series of windows onto that powerful and contradictory dream that has made it a reference—and a model—in the West. Likewise, the exhibition America, Between Dreams and Disenchantment invites us to reflect on a dream that still concerns us as spectators of the American arc. It is not an epitaph, but perhaps a moment of critical hesitation. Geraci, together with his illustrious predecessors, urges us not to simplify, but instead to take to the road, to look closer, in an attempt to understand—or at least to define the boundaries. To look as a choice, as a poetic and understanding act.

America, Between Dreams and Disenchantment

21.9 – 23.11.2025

Selected works from the Dionisio Gavagnin Collection and photographs by Valerio Geraci

Curated by

Steve Bisson e Dionisio Gavagnin

Orari

Sunday 4:30pm–7:30pm

On Friday, September 19th at 9:00 PM, in Treviso, Lab27 will inaugurate its 2025/2026 exhibition program with America, Between Dreams and Disenchantment, a show that questions what America still represents today for the Western imagination—an imagination that continues to chase its evolutions, myths, and drifting trajectories.

The exhibition weaves together historical perspectives from the Dionisio Gavagnin Collection—an archive preserving icons of 20th-century American photography—with more contemporary visions from American Eden by Valerio Geraci, who, since 2016, has been driving across the United States in search of the essence, contradictions, rugged beauty, and myth-making force that has fascinated him since childhood.

This is not a linear exhibition, but an elliptical vision, made up of counterpoints, echoes, and connections between past and present. A visual vocabulary built around concepts that for decades have fueled literature, cinema, and above all photography—and which today seem to have reached a critical turning point.

The Pioneer Spirit. It begins with the journey into the unknown: the myth of the frontier, the wagon and the horse as archetypes of a founding epic. A diptych pairing Walker Evans (1933) and Geraci (2023), ninety years apart, reveals a surprising continuity of intent: a gaze towards the margins, a tension toward a truth hidden in the folds of the everyday, where a spirit of assertion and triumph resides. The aesthetic language changes, but the stance of the gaze remains.

The Promised Land. America as an original Eden: vast, open, to be conquered. A place of hope and ambition. The photographs of O’Sullivan, Jackson, Curtis, and Weston span from 1874 to 1937, offering iconic visions of a nature encountered with a calculating, probing, documentary gaze. This is a prelude to the transformation in how the world would be perceived through the machine—leading up to Geraci’s 2021 photograph, in which a ribbon of asphalt winds like a snake through Utah’s monumental landscape: a powerful image of the gradual erosion of that primal innocence.

The act of looking—manipulating, cataloging, normalizing—reappears in the serial, industrial approach of Joseph Dankowski, who systematizes vision and anticipates digital exegesis through the reproducibility of his manhole covers (1969–1971). Decades later, Geraci playfully echoes this with a vernacular shot in Saint Martinville.

The Myth of Progress. From conquering the land to conquering asphalt: progress, as a salvific narrative, is questioned through images showing the alienating transformation of the landscape. Robert Frank’s (1955) anonymous parking lots of postwar commercial settlements give way to Geraci’s equally desolate tourist lot near Nevada’s Hoover Dam (2016). Already in 1947, Esther Bubley took us aboard a Greyhound bus—symbol of a coast-to-coast America—where travel becomes transit in a geography already colonized by the gaze.

But there is another speed: that of those who do not take part in the race, or are excluded from it. The man in Elliott Erwitt’s North Carolina photograph (1950) and the one Geraci captures in Louisiana (2018) could be the same: hat, white shirt. A temporal diptych balanced by Mydans’s 1936 portrait of a couple in a stark rural Ohio interior. Once again, the provinces—the same that Geraci traverses—not by chance, but by choice: because here the heartbeat of deep America is most authentic and most overlooked.

When the Myth Becomes Symbol. In 1978, Joel Meyerowitz photographed a McDonald’s sign next to the American flag: two superimposed icons marking the shift from collective dream to individual consumption. The dream has been co-opted by hamburger culture—now brand, consumption, industry. Decades later, Geraci records its stubborn persistence: another McDonald’s, in Yuma, Arizona, where the landscape has been bent to a functional, homogenizing grammar. Here, the figure of a father—undressed in the half-light of a Tennessee motel room (2017)—becomes a meditation on the human condition, much like the bare gaze of Kee, a boy reclining before Nan Goldin’s lens (1988).

Television as a tool for shaping the masses and disseminating the myth—once the queen of the living room and the collective imagination. Stephen Shore’s TV (1975) is centered in the frame, dominating the scene. In Geraci’s work, however, it’s relegated to a vacant storefront in Mississippi (2017), tucked in a corner: switched off, forgotten, supplanted by the pocket-sized stream of social media. The intrusion of television as a prelude to the dematerialization of imagery under the panopticon of Big Tech.

For some, the American Dream is now a mirage—or a source of protest. In Joe Deal’s 1978 photo, the abstraction of a roadscape foreshadows contemporary chaos, a deranged cartography echoed in Geraci’s overturned car in Nebraska (2018), stranded off-road. In 1975, Lee Friedlander wryly confines monumental America to a traffic circle—an involutionary historical loop. Joel Sternfeld, in 1984, shows us the face of a blind man in Alaska’s outposts, surrounded by a lush garden he cannot see—anticipating the paradoxical mood of a West at sunset, edging into darkness. The gaze of a middle-aged man Geraci meets in Wyoming (2017) turns elsewhere—away from the photographer, away from the photograph—seizing, in its intensity, the blue of the skies.

In 1965, Diane Arbus photographed a family at a nudist competition: the dawn of a body revolution. A body that would be legitimized, commodified for entertainment. Today, that body is spectacle, product, performance. Geraci’s Texas cheerleaders (2018), dressed as cowboys and bathed in golden light, seem to stage a new choreography of desire and conformity. Between eros and marketing, the individual has become their own image.

Family and Home. Foundational symbols of the American bourgeois imagination. Dorothea Lange (1935) captures, in the midst of the Dust Bowl, a family along the highway: uprooted yet united in desperate togetherness—tragically real. In 1972, Bill Owens takes us into suburban America, where the aspirations of the middle class find refuge and expression. And, in his own way, Geraci encounters a family and a home in Brady, Nebraska (2023), photographing them in the intimacy of Christmas decorating: a moment at once sacred and profane, reassuring and precarious—a reminder that family stability is fragile, yet capable of withstanding unforeseen challenges.

Valerio Geraci’s editorial project American Eden does not claim to offer an exhaustive reading of America, but rather opens a series of windows onto that powerful and contradictory dream that has made it a reference—and a model—in the West. Likewise, the exhibition America, Between Dreams and Disenchantment invites us to reflect on a dream that still concerns us as spectators of the American arc. It is not an epitaph, but perhaps a moment of critical hesitation. Geraci, together with his illustrious predecessors, urges us not to simplify, but instead to take to the road, to look closer, in an attempt to understand—or at least to define the boundaries. To look as a choice, as a poetic and understanding act.